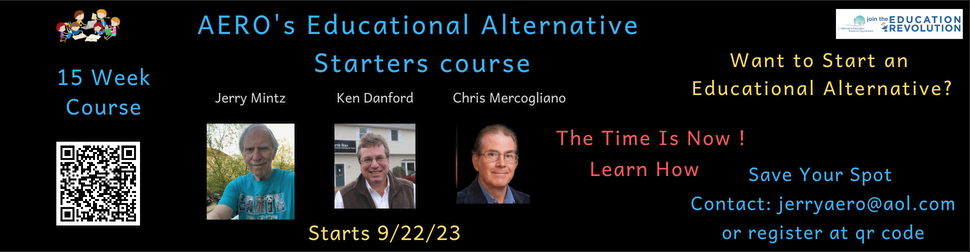

By Chris Mercogliano

Ed: Chris Mercogliano was also in Denver with his school group when when the Columbine tragedy occurred. He’s an author and the former director of Albany’s Free School.

Will we remember where we were the day the Littleton massacre went down, like those of us from a generation ago when JFK was shot? I hope so. Though it’s only the latest in a string of school mass murders, we must make this tragedy the one that freezes time long enough for the information encrypted in the event to be decoded. We have got to get the message. Enough is enough. So much has already been said and written about the tragedy. The Tom Brokaws and the Times and Newsweek’ quickly turned it into the Littleton Show. For days afterwards the Denver dailies featured entire special sections on the killers and their victims. But as the immediacy begins to fade, will the public discourse move beyond the hype, the hysteria, the scapegoating, the layers of denial into some deeper understanding that might help prevent another such disaster? If history is our guide, then there’s little reason to be optimistic. How does one come to terms with the causes of such an abominable event?

There are so many areas to search for reasons and contributing factors: the psyches of the killers, their parents, the surrounding culture, the ready availability of high – powered weaponry, and always at the bottom of the list, it seems, the school. This is where my attention remains, not because I believe it is the school’s fault that the blood of dozens was spilled upon its tiled floors, but because this is where no one wants to take that long, hard look. Education, you see, is our most sacred of sacred cows. The system is built upon a mountain of assumptions, notions that we don’t even question anymore such as compulsory attendance and learning, age segregation, rating and sorting students by performance — pitting one against another, punishment for non – compliance, exclusionary labeling for non – conformity, and a hierarchy of authority. The list could go on.

Even the students are buying into the prevailing mythology. This I discovered when I happened to catch a snippet of a talk show featuring a group of Columbine students. The subject was cliques, a very relevant topic since the killers had made it all too clear that revenge for their outcast status was one of their primary motives. Cliques, reflected each student commentator, are a natural ingredient of high school life. Everybody belongs to one.

I beg to differ. Cliques are a stress response, a symptom. When humans feel threatened, the most primitive portion of the brain (the reptilian brain) takes over. The reptilian brain concerns itself with survival, with defending its turf, with dominance over rival groups. Teenagers join cliques in school because their schools are hostile, high – pressure environments, places of overcrowded captivity, competition, judgment. Their motivation, rarely conscious, is security, and a sense of identity and belonging. Just like urban youth gangs. Cliques are anything but natural. Even if a hundred Frenchmen belong to them, it doesn’t make it so.

I’LL NEVER FORGET WHERE I WAS WHEN the surreal, manic killing began. As fate would have it, I was only five miles up Wadsworth Boulevard on the outskirts of Denver, visiting the public high school in the adjacent suburban enclave known as Lakewood. We had just arrived, ten seventh and eighth grade students and three teachers from the Albany Free School. It was a cool late – April morning. High, wispy cirrus clouds signaled an approaching snow storm. A big one, they were saying. Our itinerary had us spending a day and a night at the Jefferson County Open School, a stopover on our way to the National Coalition of Alternative Community Schools conference being held about three thousand feet above Denver on the edge of the Continental Divide.

Just before lunch I went into the library to read over a friend’s manuscript, while our kids were in the gym unwinding from the thirty – six-hour train ride. I was immediately puzzled by the number of school staff huddled around a TV set in the librarian’s office. And there was a strange mood attached to the scurrying in and out, a concern so hushed that it seemed out of place even in a library. People had initially been so friendly. Now all of a sudden I seemed to be invisible. Finally, the librarian noticed me and came quietly over to the table where I was working and wondering what was going on. She diplomatically clued me in on the unfolding madness.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Not again.

As the initial media chaos slowly sorted itself out, it became clear that this was the worst ever. God help us if they ever come up with a Richter scale for school violence. By 2:00 PM the horrible news had whispered its way through Jefferson County Open. I watched teachers and students alike slide into a state of semi-shock. They all knew someone at Columbine High. And they must have all been thinking silently to themselves, “Could this have happened here?”

I FOUND MYSELF INWARDLY POSING THE VERY SAME question. An answer came quickly. No, I don’t think the brutal attacks would have occurred at the Jefferson County Open School because it is a very different kind of school, a publicly – funded alternative founded in the early seventies on a very different set of principles. To begin with, JCOS is smaller (fewer than a thousand students) and it spans all twelve grades instead of just the usual three or four. It truly is an open space, architecturally and otherwise. While I was there I observed students strolling the halls without passes. They chatted informally with their teachers and called them by their first names. Many of them were working independently on projects, both academic and artistic. Grades didn’t appear to be the prime motivator either. The students were enjoying what they were doing. And they clearly had a say in the life of the school; in fact, before the end of that awful day a senior was already busy organizing a student meeting to address the crisis at Columbine. This was her own idea. She wasn’t going to get extra credit for it. Here was a spontaneous expression of ownership and responsibility — and caring.

By the way, I saw no evidence of cliques while I was there. Graduation from JCOS isn’t based on the compilation of credit s. Instead, students must successfully complete seven “passages,” each designed to demonstrate the mastery of a skill that is integral to living a good life. Self – assessment counts as much as the teacher’s. Above all, this genuine alternative to conventional schooling, which is a model based on centralized control and Skinnerian rewards and punishments, is a community of sorts. Not the euphemistic kind, like the “Italian community,” or the “academic community,” but a real community based on commonly held concerns. Faculty and students have a collaborative relationship. They meet together as a whole body once a week to discuss issues of relevance. This differs from most so-called “student councils,” which include only a chosen few, are merely symbolic of democracy, and tend to deal in trivialities. The truth of the matter is that students in conventional high schools have no power whatsoever. And they know it.

One last, very important detail: every student at Jefferson County Open has a mentor, so that no one goes unnoticed. Each child is valued for his or her personhood. Contrast all of this with what John Taylor Gatto recently reported to me. Author of Dumbing Us Down and outspoken critic of the tyranny of compulsory education, he received several phone calls from Littleton residents in the aftermath of the tragedy. More than once he was told that students escaping the bloodbath at Columbine were heard to have said when they reached safety, “We’re only products there; that’s all they care about.” Funny, I don’t remember reading that in Time magazine.

OF COURSE I CAN’T REALLY CLAIM with any authority that the massacre couldn’t have occurred at Jefferson County Open. A member of the staff there shook her head from side to side when I shared this thought with her late in the day, saying, “There are a couple of students here that I worry about. They are angry and defiant a lot, and don’t seem to care about anything.” “But,” I responded, “you’re aware of those kids. You and your colleagues are paying attention to them.” This time she nodded affirmatively. “And besides,” I continued, “there’s an insufficient level of tension and animosity in your school to provoke such a monstrous act.” Another nod.

I refuse to accept the idea that the Columbine killings were a random act, the isolated handiwork of sick individuals. The perpetrators’ choice of setting in which to vent their murderous rage was thoroughly premeditated. This fact has been documented ad nauseam. They harbored deeply held grievances against their fellow students and the social climate of their school that had gone ignored for years. They left a trail of warnings that no one picked up on. God help us if we ever discover that such inhuman behavior just springs up overnight, out of nowhere. That is not a world I would want to inhabit, or raise children in.

No, I firmly believe that mass murder will never take place at Jefferson County Open School, or any school where relationships and interconnectedness are fostered, where the work is meaningful and cooperative, and where everyone feels they belong.

Here is my short – take on the Columbine murders: It’s another case of “kid – on – kid” violence. Just as the killing of black males one by another in the nation’s ghettoes has been identified by some as “black on black” violence, all of the school shootings are on a certain level examples of kids aiming (quite literally) their venom and frustration at each other, rather than at home, school and society where it rightfully belongs. So often the oppressed attack each other instead of joining forces against their oppressor.

WHAT ARE THE TEACHINGS OF THIS TRAGEDY? I ask the question because if we can learn enough from this one to prevent yet another, then those young people will not have died for nothing. Consider the words of Marcy Musgrave, from a column she wrote for the May 2 edition of the Dallas Morning News. A junior at Texas A&M University, she proposes that her yet – to – be – named generation, which follows Generation X, be called Generation Why. Explain s Marcy (formatting changed for this article):

After the massacre in Littleton, I realized that as a member of this generation that kills without remorse, I had a duty to challenge all of my elders to explain why they have allowed things to become so bad … Why did most of you lie when you made the vow of ’til death do us part?

- Why did you fall victim to the notion that kids are just as well – off being raised by total strangers at a day care center than by their own mothers or fathers?

- Why is work more important than your own family?

- Why does the television do the most talking at family meals?

- Why is money regarded as more important than relationships?

- Why is “quality time” generally no longer than a five – to 10 – minute conversation each day?

- Why do you try to make up for the lack of time you spend with us by giving us more and more material objects that we really don’t need?

- Why haven’t you lived moral lives that we could model our own after?

- Why do you allow us to spend unlimited amount s of time on the internet but still are shocked about our knowledge of how to build bombs?

- Why are you so afraid to tell us “no” sometimes?

- Why is it so hard for you to realize that school shootings, and other violent juvenile behavior, result from a lack of your attention more than anything else? Rude awakenings like the Littleton massacre probably will continue until you begin to answer our questions and make the changes to put us, your kids, first. You might not think we are worth it, but I guarantee that Littleton will look like a drop in the bucket when a neglected Generation Why comes to power.

Tough insights from one so young. I am a parent of teenagers and I could feel the sting of every lash-like question. Why indeed. Perhaps Marcy was among the fortunate minority who was homeschooled or who attended schools that were on her side, so that her penetrating gaze passed over our institutions of education and the invisible ways in which they impact American youth. Bu t mine won’t because I work with children every day, many of them rejects and refugees of the system. And my eldest is just finishing her second year at our local public high school, which I suspect differs little from Columbine, except in the demographics of the students. I am one of the fortunate dads whose daughter doesn’t just answer “Fine” when I ask her how things are going in school. She tells me how “stressed out” her teachers are. Only one or two ever take the time to speak to her individually. Instead, everyone’s mantra is, “You’ve got to hurry up and get ready for the state exams.” It was my daughter’s choice to go to our centralized, citywide high school. She wanted to be in a diverse setting with all different kinds of kids. And yet, despite her outgoing nature, in two years she hasn’t made all that many new friends. There isn’t any time or opportunity for socializing. They are kept interminably busy. The halls are crowded and under constant surveillance by hall monitors and cameras. The students are separated by rigid routine and endless competition. Nothing facilitates their getting together.

My daughter, an honor roll student, one of two sophomores in a class of over seven hundred and fifty to be nominated for a statewide award, is seriously considering quitting. She has my blessings. Inspired by Marcy Musgrave, I will leave you now to ponder my questions about schools:

- Why have we let our schools become warehouses for youthful energy, creativity and purpose — why have we so walled them off from the outside world?

- Why have we turned teachers into overwhelmed taskmasters, instead of enabling them to serve as mentors, guides and role models?

- Why have we allowed schools to become so hyped with standards that they pay no attention to the emotional well – being of our children?

- Why have we let them turn education into the regurgitation of homogenized data, rather than a search for knowledge based on experimentation and real experience?

- Why isn’t learning a cooperative enterprise, and why aren’t students included in the design and the maintenance of the system?

- And the corollary, why do the schools maintain internal status structures that ape the larger society and that fuel the drive to split off into separate, exclusive groups?

- Why do we accept the level of fear that surrounds the learning process?

- Why do we permit schools to corral our children into a state of sheep – like anonymity?

- Why are teenage expressions of boredom, anger and alienation only met with intensified management and control?

- Why do we go on believing that our schools just need minor tinkering, rather than a fundamental reevaluation and revisioning?

DO I THINK COLUMBINE HIGH SCHOOL caused the tragedy that occurred there? Or those two young men’s parents? Absolutely not. This is no time for blaming. It’s an occasion for deep reflection, for three – and four – and five-dimensional looks at the whole picture. For questions that don’t receive fast, unilateral answers. As I consider one last time Marcy’s challenge to parents and mine to schools, I think I detect a common denominator: attention. Isn’t that the core of the message, that Generation Why is crying out for attention, and that the two most likely sources, home and school, are altogether too reluctant or preoccupied to provide it? But, as Marcy warns, we’d better start paying attention soon.