By Yan LI

From the oldest continuously running democratic school Summerhill founded in 1921, till now, democratic education has developed into a global movement, from kindergarten to high school. There are a number of democratic schools at the pre-school, primary and intermediate levels but at the higher levels, there are less. I was then curious to know how are the principles of democratic education implemented at the university level?

Shure University in Tokyo is a 27-year- old college where students have the freedom to choose what and how they learn and where they use a democratic decision-making process among students and staff. Mr. Kageki Asakura is one of the founders of Shure University. We met at the First Asia Pacific Democratic Education Conference (APDEC), which was held in the Holistic School, Miaoli County in Taiwan from July 18 – 24, 2016. During this conference, keynote speeches in the morning were given by appointed speakers and after that, most time segments were open space where anyone can sign up and share their own experiences in workshops, discussions, and other formats.

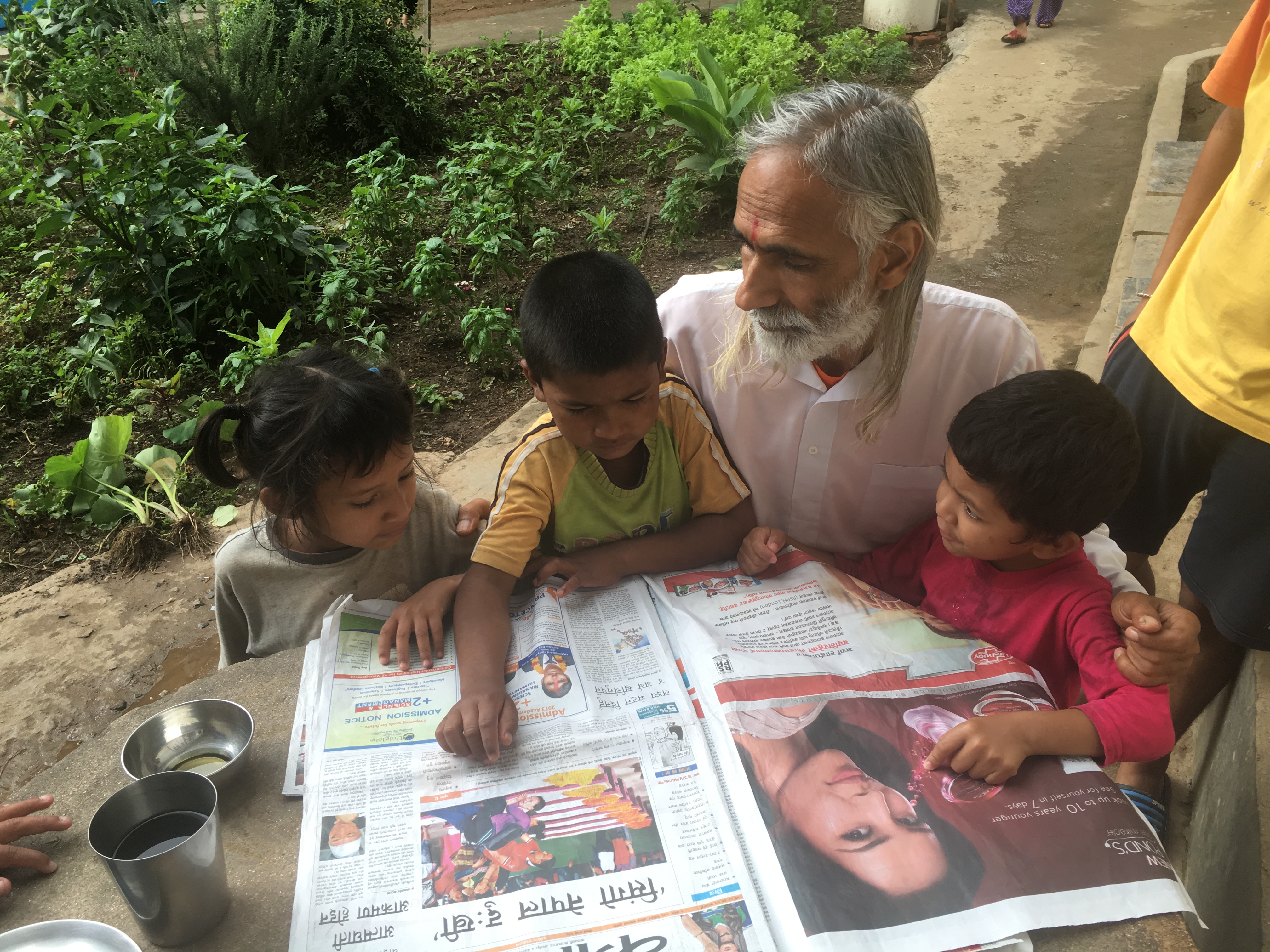

During the keynotes, Mr. Kageki interpreted the speeches to the students who gathered together and listened intently. On the 22 nd , Japan Democratic School network held an Open Space about “Japanese School Refusal and the Democratic School Network Movement.” Apparently, school refusal in Japan is a huge issue in the field of education. Many democratic school students go through the process of school refusal. In the beginning, the students who went through this process themselves, explained what school refusal is, why the students refuse to go to school and how the democratic schools meet the student’s need. They don’t really refuse school for economic or health reasons but for deeper reasons that question their sense of self, their values and identity.

One student shared her own story: at the state school she felt bored and was under pressure to perform because everything was measured by how one’s accomplishments compare with the others. There were expectations which she had to try and live up to. She refused to go to school. At nineteen years old, she went to Shure University and spent one week trying it out. During that short experimental period, she realized what was taken away from her – that idea that it’s okay to pursue something you are interested in. That idea empowered her to alter her self- perception and turn her life around. From somebody who did not believe in herself and had a very low self-esteem, she became self-assured and motivated to pursue her own unique path in life (https://entirelyofpossibility.wordpress.com/2016/07/28/opening-up/). At the APDEC, she went on stage to express her idea of offering her photographs for sale at the fundraiser. She was active, confident and creative in front of the participants. In another open space, Shure students presented the Japanese tea ceremony, paper folding, self-designed stamps and so on which attracted a lot of participants. I was impressed by their kind, caring and calm smile and then began to gather more information about this democratic university.

In Shure University brochures, it says: “To live as I want. To get the world back to the self. To study, to express, to be reborn.” Shure Tokyo is the parent organization of Shure University, an non-profit organization founded by students in 1999 who wanted to continue their education. There are no qualifications necessary, no pre- defined curriculum, only freedom. In China, students are measured according to their academic performance at a college entrance examination. We judge students by the grades they get, not by who they are. We have a compulsory curriculum. If the students fail, they can’t get their degree.

“Accepted” is a 2006 comedy film made in the United States about a group of high school seniors who, after being rejected by all colleges to which they had applied, create their own college, the South Harmon Institute of Technology (https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Accepted_(film). The students decide what they study based on their own individual schedule, how to spend their tuition, how long it takes to finish the course. They don’t have traditional teachers, classrooms or library, however they find their creativity and passion for learning with a desire for self- growth. Ironically, true learning takes place in this fake college. The students don’t need society’s approval to tell them what to learn or how to learn. It’s about total self-acceptance. When I introduced this American film to my students in Psychology class, they began to feel inspired, but later they said it was just a movie and not real.

Reality

I was eager to see how the concept of democratic university works in real life. Not long after the conference, on August 4, 2016, I visited the Shure University in Tokyo. Located in a two-story building, including one room for teenage democratic students, Shure University put the dream of democratic education into practice. Although that day fell on their summer vacation, the staff and students of Shure University were busy preparing for the Shure University International Film Festival all the way until night time. It was to be held a few weeks after so as the students labored, Mr. Asakura showed me around the building and patiently answered my questions.

Philosophy

Shure is an ancient Greek word, which means a place where people can use their mind freely. Mr. Asakura and his previous democratic school students started Shure University, because the students didn’t want to go to the traditional university to further their study. They wanted to continue the practice of making democratic decisions about the way they learn, including the tuition they pay, the curriculum they cover and the years they spend in college. Before establishing the Shure University, Kageki had already been teaching at free schools for decades and taught sociology at the University.

In Shure University’s website, the philosophy behind their school is best embodied in the phrase “creating your own way of life.” Society usually expects people to graduate from high school and university, get a job and be a productive member of the community. Democratic education posits that this is not the only route to take. “Changing yourself to match society’s expectation is only one way to live. Another way is to create your own values through your own interests and experiences for the purpose of suiting your own lifestyle. How do you want to work? How do you want to spend your time? How do you want to build relationships with others? Students here try to create their own values with other students, staff members, advisers and other friends of Shure University.” (http://shureuniv.org/english)

Administration

Now, there are around forty students, four staff members and almost fifty professional advisers from various fields. In the end, the students in Shure University do not receive a degree. Why then do they choose to attend? For them, education is about true learning, and not merely a certificate. The tuition cost is higher than the state universities but below the private ones. Without recognition by the Japanese Ministry of Education and comparatively low tuitions, Shure University has no economic advantage to attract famous experts to teach here. However, there are still fifty professional advisers such as Serizawa Shunsuke, Hirata Oriza, Shin Sugo, Hau Yasuo, Ozawa Makiko, Ueno Chizuko. The university attracts the people that they do because the students are highly self-motivated and tend to excel in the things they do since they choose it themselves.

Referring to the advisers, Mr. Asakura said that “We need fifty of them because interest of students are so diverse.” Even though the school only has forty students, the interests are so broad, spanning philosophy, anthropology, music, law, drama, cinema, history, documentary and others. These also change over time so the university has to be ready to deal with the evolving interests. Sometimes, the adviser comes to the university to hold a workshop or a class while other times, the student can visit the adviser’s office to have a personal tutorial or consultation.

It is understandable how diverse the composition of experts and advisers are because there are many unique courses available in Shure including: Alternative Education, Academic History, School Truancy, Family Discourse, Life Discourse, Cultural History, Politics and Economics, World History Research Seminar, Creating Your Way of Life, Literary Discussion, Pop Music, Computer Science, Tokyo Cultural Activities, Live Theater, Modern and Fine Arts, as well as language classes such as English and Korean. Project-based classes are also available including Film, Drama, Music and How to Build and Race Solar Powered Cars (http://shureuniv.org/english).

Evaluation

There are unique personal courses and a number of group projects. Students here decide how many classes they have and how many years they attend. They explore their own path with other students, staff members, advisers and other friends of Shure University. The graduate is evaluated on individual and project-based performance. One of the Shure University students, Yui Sakamoto explained that there is a meeting each semester to discuss and reflect on the seminars and group projects, what they want to get during the present semester and what they got during the previous one. Each student has tutorial time when they talk about their individual plans and reflect on their own work. Each student makes a presentation around March including an evaluation of their own work while other members give a response or comment on the presentation. They don’t use numerals to evaluate anything or anyone. In a sense, according to Yui Sakamoto, this is more challenging so when she needs to get a deeper understanding, she has to ask questions to grasp what she wants. For her, the most important thing is “living her own life and making the kind of world that she wants.”

At the APDEC 2016, American psychologist Peter Gray, author of Free To Learn explained how he would evaluate an educational system based on two questions: 1) Are the students happy? and 2) Do they live satisfying lives and are productive in society? (https://entirelyofpossibility.wordpress.com/2016/07/28/at-the-roundtable/) From this perspective, the graduates of Shure University seem to fulfill these standards. The majority work at an NGO or take care of senior citizens. Almost none of them takes part in the commercial field. They become responsible, caring adults.

The next APDEC will be held in Tokyo at The National Olympic Youth Centre on August 1 – 7, 2017. People from the Shure University will actively be involved in organizing this major, international event. Joining it may be an ideal way to continue learning more about this exceptional university and about democratic education in general.

About the Author:

Donna (Yan LI) is a Educational Psychology Lecturer at the School of Communications, Tianjin Foreign Studies University. As much as she possibly can, she wants to promote the ideas of democratic education and hopes to start a Democratic School in mainland China someday.